What are inversions and why should you care? Inversions allow you to play a chord ANYWHERE across the keyboard so you can choose what fits best for every situation.

This article accompanies my YouTube video of the same name:

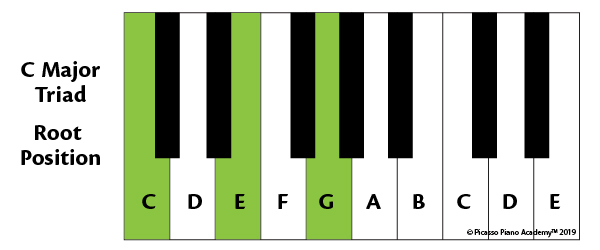

Usually when you first learn a chord, you learn it in the root position (see image above). This is a good place to start, but eventually you’ll get tired of playing a chord the same way every time. And your listeners might start to get bored as well (though they may not realize why).

Inversions are different ways of “stacking” the notes of a chord in different combinations—also known as voicing. Inversions give you more options for easier hand positions, for blending well with other instruments, and for improvising all across the keyboard.

Quick Review:

- Chord: a group of three or more notes played simultaneously.

- Triad: a chord consisting of three different notes.

- Root note: the primary note of a chord, i.e., the root note of a C Major Triad is C.

As you can see in the illustration up at the top, the lowest note in the C Major triad is the C note. That is why this voicing of this triad is called a root position triad.

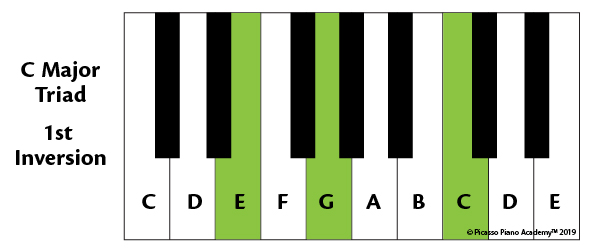

But what if you take that C note and move it from the bottom of the stack to the top of the stack? The chord is still a C major triad, but the order of the notes has changed to E-G-C. When we stack the notes this way, with C on top, it’s called a first inversion C Major Triad:

You’ve probably already guessed the second inversion. Move the E note from the bottom of the stack to the top. Now the order of the notes has changed to G-C-E. Once again, we still have a C major triad, but now it is in the second inversion C Major Triad, like this:

So now we have three options for playing a C major triad within any octave.

Learning these inversions increases your options for the C major triad from seven root position triads across the keyboard, to twenty positions when you know how to construct all the root position triads and inversions available.

Freebies and Extras:

Here’s a free transcription of the intro and ending snippet you see me playing in the video. This is an exercise that uses inversions of two triads, C major and F major (“C” and “F”). The triads are “arpeggiated”, which means playing the chords one note at a time.

To get started with inversions, pick a major triad. Eventually you can learn all the triads, but C major is a good place to start. (Once you get the hang of it, you can use inversions for all your chords, not just C, not just triads, not just major chords.)

Figure out how to play that C major triad in every possible inversion—three per octave—all across the keyboard. Over time, your hands will find the inversions automatically without you even having to think about it.

Next, try F major. Figure out how to play F major in every possible inversion—three per octave—all across the keyboard.

The next step is to alternate between C major and F major inversions all across the keyboard (see video for demo).

Practice alternating between C major and F major while keeping one finger on the common note (“C”) in both chords. Which inversions of C major and F major can you play with your thumb on C? Which inversions of C major and F major can you play with your pinky on C? Which inversions can you play with your index finger on C?

Once you’ve got this figured out, try it with a metronome or a drum track from YouTube.

Next, try adding G major to the mix, alternating between C, F, and G major chords.

Inversions and Hand Position

Inversions allow you to find the most convenient place to play a chord, based on where your hand is at any time. Suppose you need to play a C major. If you only know the root position, then you have to move your hand to that position in order to play the C major.

But if you know the inversions, you can choose the C major position that is already underneath your fingers, allowing you to move much more quickly and smoothly between chords.

Inversions and Jamming With Other Instruments

Most of the time, the rhythm guitarist is chunking around in the mid-range around middle C and the octave below. As a keyboardist, you’ll typically want to get out of that area because it’s already being used. You don’t want to have a build up of frequencies in the same range, when you’ve got plenty of options above that on the keyboard.

Being conversant in inversions let’s you go wherever you want to go sonically to blend well but not compete with what the other musicians are doing, allowing the band to create a musical tapestry of many threads.

Imagine you are weaving a tapestry with complex patterns, but all the threads are the same color. The tapestry will look very plain. But when you vary the colors in interesting ways, the complexity of the woven patterns emerges.

Sounds work the same way. All the musicians may be playing the same notes and chords (hopefully!) but by varying the octaves, inversions, and rhythms, patterns emerge that captivate listeners.

Inversions and Improvising

Inversions keep things interesting when you’re improvising. Changing up your chords by playing different inversions makes your improvisation more interesting and complex. Also, by playing chords and inversions one note at a time (arpeggios) you will expand your lexicon of options for soloing. Check out the intro in the above video for an example. Here’s a free transcription of the riff.

Inversions work for other chord types too. Minor triads, 7th chords, 9th chords, and so on. As you add more chords to your toolbox, you can add the inversions for those chords as well.

Inversions can also be used to create arpeggios when improvising—just play the notes one at a time rather than all together. Check out the intro in the above video for an example. Here’s a free transcription of the riff.

I WANNA LEARN FROM U!

Great!. Keep at it. Check out my YouTube channel too. Private lessons are available via internet (see email on contact page).